#pathtozerocarbon, #sustainability

03 – Toward Zero Carbon Architecture

With the built environment responsible for over 40% of human-caused carbon pollution globally, the design and construction industry is racing to decarbonize toward zero carbon architecture – balancing pollution with carbon negative activities. ‘Zero’ is deceptively simple, but so far carbon neutrality claims and certifications are only true under a small set of circumstances and within very limited boundaries. This post will explore expanding the boundaries so we can track real progress toward zero carbon architecture.

On-site solar energy is an important piece of zero carbon architecture but balancing annual energy use to zero is only one of the efforts necessary to get there.

The Sun Provides All the Energy We Need

We can now power nearly all human activities with clean energy from the sun. The earth receives more solar energy in 60 minutes than humans currently use in a year (and most fossil fuel energy we use is wasted). For example, solar panels on roughly 10,000 square miles could provide all of the power the US currently uses annually, which is significantly less land than the oil and gas industry currently uses. This includes energy for heating, air conditioning, cooking, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and the rest of it.

Energy from the sun can be harvested in many ways: it powers photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, hydro, grows much of our food, and provides daylight and passive heating for buildings. Fossil fuels were also created by the sun millions of years ago, removing carbon dioxide from the air and trapping it underground, which created the conditions in which humans have thrived over the last thousands of years.

Electricity generation from cheap and clean sources such as wind, solar, and batteries is a radical technological advance. Similar to historical transitions from burning wood to coal, then to oil and gas, the transition to electrification vastly increases the amount of energy we are able to generate and use, remaking what we are able to do. New options include the independence of generating cheap and clean energy on buildings sites and reaching annual net zero energy. This transition enables net zero carbon for advanced buildings and communities, and eventually economy-wide.

Solar energy is also freely available. While the current energy system is controlled by a small number of very profitable companies (primarily fossil fuel and utility companies), no one owns the energy from the sun. It is a source of energy independence from large incumbents.

Electricity can be used directly for nearly any energy need, large quantities can be transported long distances easily, and with inexpensive batteries now it can be stored at scale. Without the downsides of air pollution, climate change, and significantly less mining/extraction, the transition to a solar energy powered electric economy is in motion all over the world. The speed at which the electrification transition happens has significant consequences.

Net Zero Energy and Beyond

For the past 50 years, the buildings industry has focused on energy efficiency as a proxy for action on pollution and, more recently, climate change. Energy efficiency is still good design: controlled daylight and solar heat gains, a well-insulated and airtight envelope, efficient mechanical systems. Energy efficiency has worked, evidenced by total building energy use decrease in absolute terms by 16% even while nearly doubling of US floor area over the last two decades. Efficiency, paired with abundant and cheap solar, means annual net zero energy is widespread.

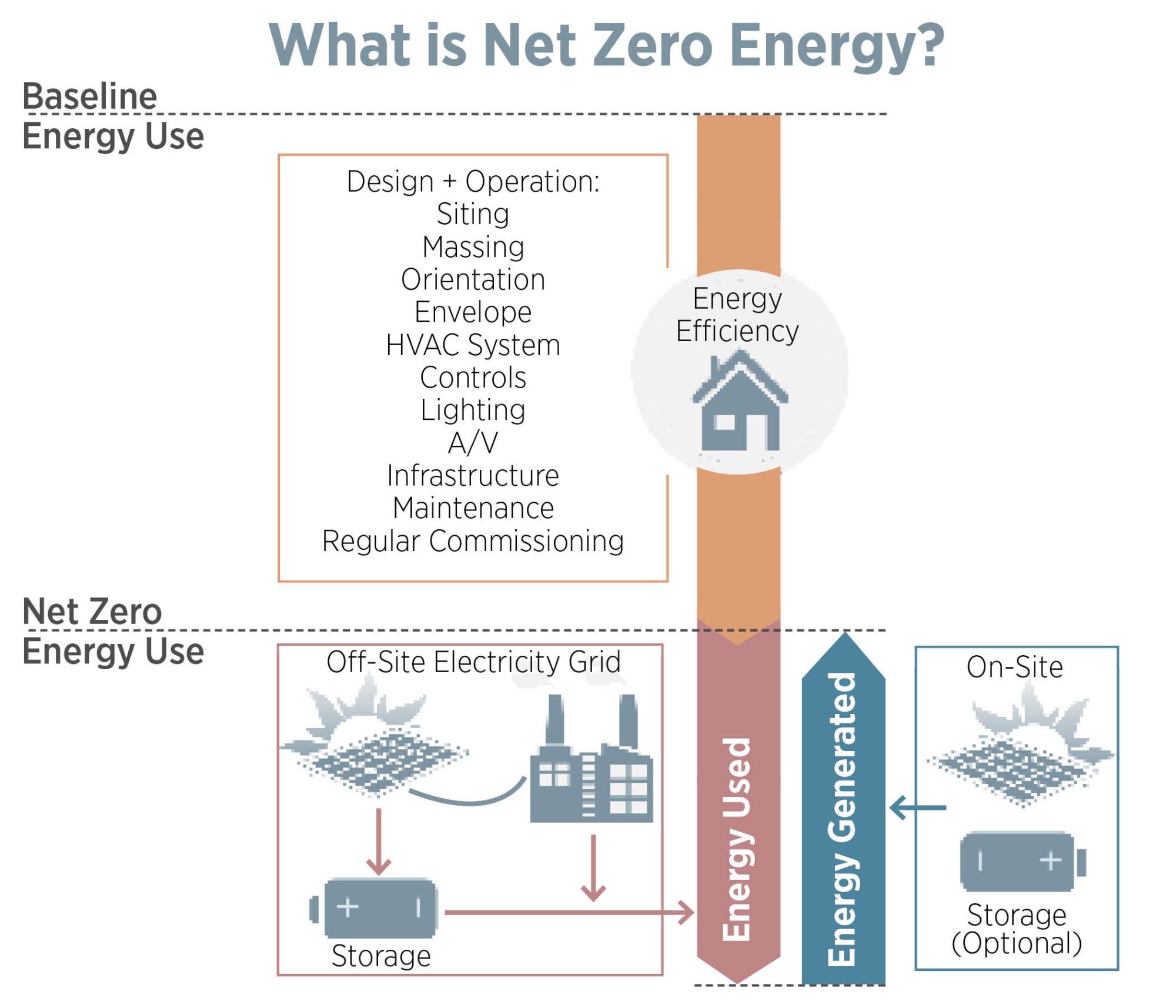

Net zero energy is often calculated by adding up all energy used over a year and subtracting all of the renewable energy generated over that year. While this is a very useful goal, it does not represent operational carbon neutrality.

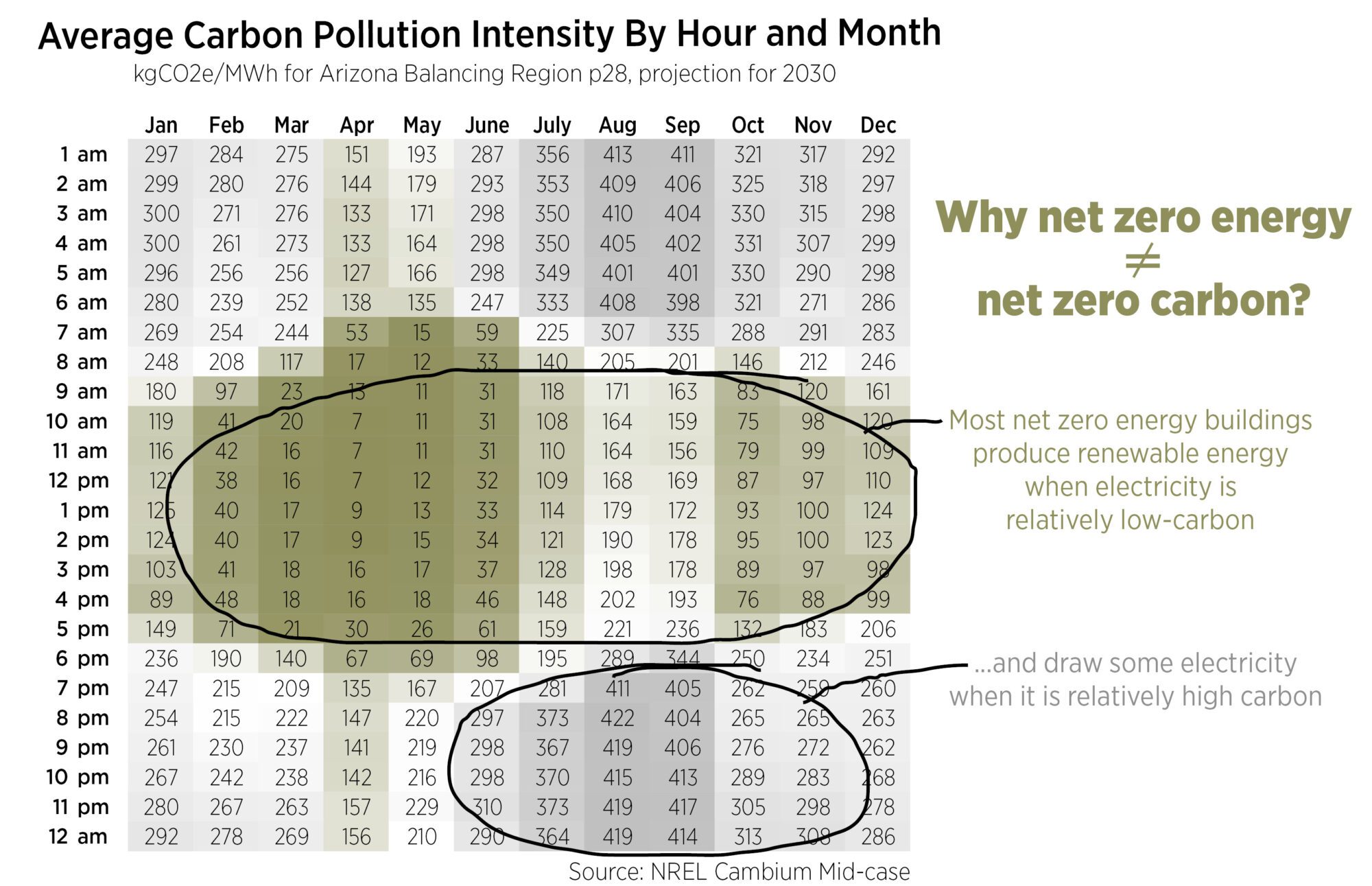

Net zero energy however, is not carbon neutrality – even when only considering energy use carbon pollution. Why? Net Zero Energy (NZE) buildings typically draw electrical power during times when less renewable energy is available and the grid uses carbon intensive “peaker” plants – fossil fuel power plants brought online to temporarily handle peak electricity loads. Including time of use carbon pollution means that many NZE building are not likely to be carbon neutral even for operational energy.

Average electricity carbon pollution intensity by hour and month, estimated for central Arizona in 2030. Net zero energy projects over over-generate during the day, when the grid is also generating low-carbon electricity, while they draw electricity from the grid at high-carbon times. While the annual energy balance to zero, the carbon numbers do not. Grid-scale batteries are being deployed to help moderate this.

Energy efficiency and net-zero energy are still extremely important for 5 main reasons:

- Reducing energy use reduces carbon pollution year-round

- Reduced energy demand means existing electricity generation sources can be used for electrifying transportation or industry.

- Reduced energy demand also reduces the need to build new renewable energy sources, including associated costs, embodied carbon pollution, transmission and distribution infrastructure, and land use.

- Energy efficient electric systems inch toward zero carbon every year since the electricity grid is rapidly decarbonizing.

- Electricity prices are increasing mostly due to replacing and upgrading transmission and distribution. Energy efficiency and on-site renewable energy reduces the need to upgrade these.

Annual net zero energy is common currently. This requires generating enough renewable energy to balance energy use over the course of a year, usually using the electricity grid as a battery. Off-site renewable energy can be purchased with a Virtual Power Purchase agreement for new renewable energy to balance annual energy use with energy generation (more in Post 08).

Net zero energy projects should be all-electric since nearly all renewable energy generation is in the form of electricity. Further, Net Zero energy claims should not be based on voluntary RECs.

Most carbon pollution is ignored

The materials used to construct buildings currently release substantial carbon pollution, pollution that will take decades or centuries to offset through energy use reductions. Advanced mechanical systems also contain refrigerants with high global warming potential that leak into the atmosphere. As we attempt to define zero carbon architecture, we first need to broaden our scope to include all sources of building-related pollution.

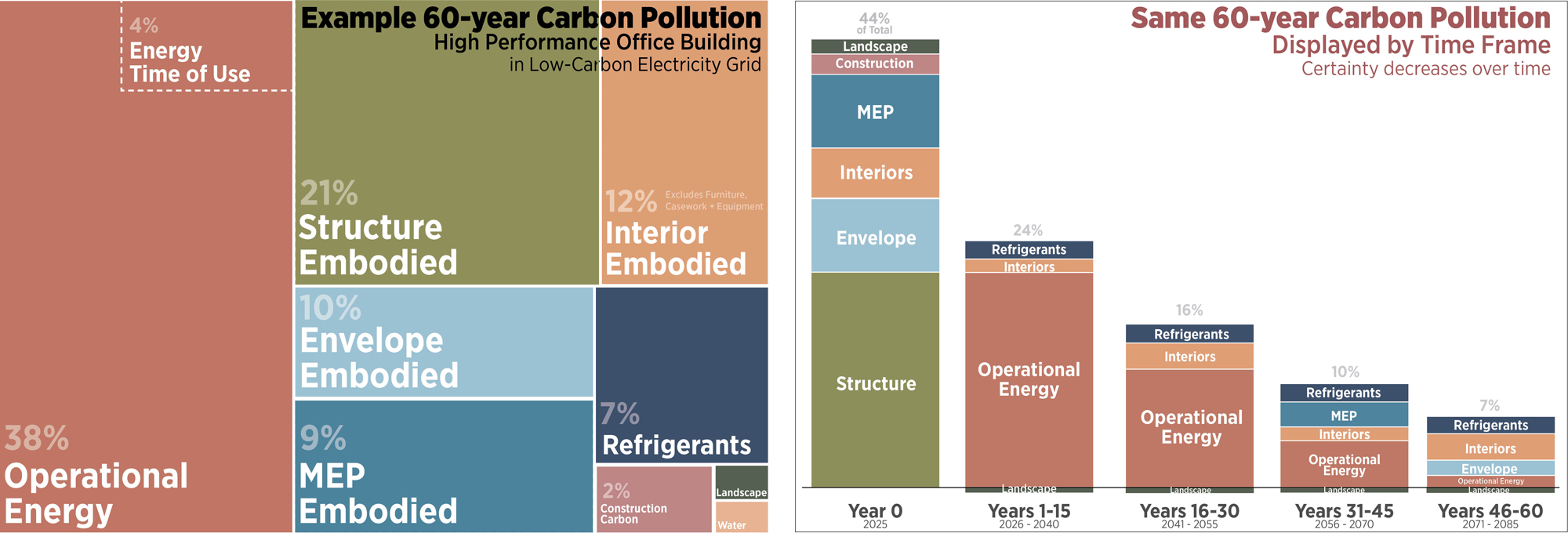

To eliminate carbon pollution, we need to understand which aspects of design cause them. To illustrate the various sources, one example project’s cumulative pollution over 60 years is displayed in the tree map (left side). While they vary significantly from project to project, in this example energy use and structural embodied carbon combine for a majority of the total, typical of many buildings.

The right side of the graphic shows the same data, sorted by time. Using timeframe as a lens helps a design team understand opportunities for near-term reductions. This also highlights that some of the pollution is far in the future, with less certainty and control of its magnitude.

60-year carbon pollution can be looked at many ways. The Tree map on the left shows an example project’s relative impacts: a majority is in operational energy and structural embodied carbon. Looking at the same project over time (right) allows us to prioritize reductions to meet time-based carbon targets set by the IPCC to reduce the risk of reaching earth’s climate ‘tipping points’. Carbon pollution in the future is also increasingly uncertain over longer time horizons, another reason to focus on near-term carbon reduction strategies.

The time series shows two more things that impact Scope 3 pollution. First, since nearly all new power plants are renewable because solar and wind are the cheapest source of electricity (and over 60% of the US electricity grid is required or pledged to be renewable energy by 2050) a 100-year building lifetime can be expected to use very low carbon electricity for most of its days. Since clean electricity is rapidly increasing at the utility scale, the only building-scale action necessary to get this reduction is to prioritize efficient electrification. Second, since structural and envelope carbon pollution primarily happens during initial construction, it is entirely in the purview of the original design and construction team. Many project teams are reducing embodied carbon from steel and concrete, and a mass timber building can have very low structural carbon pollution. Reductions across all scopes are covered in detail in posts 07-16.

What are we good at currently?

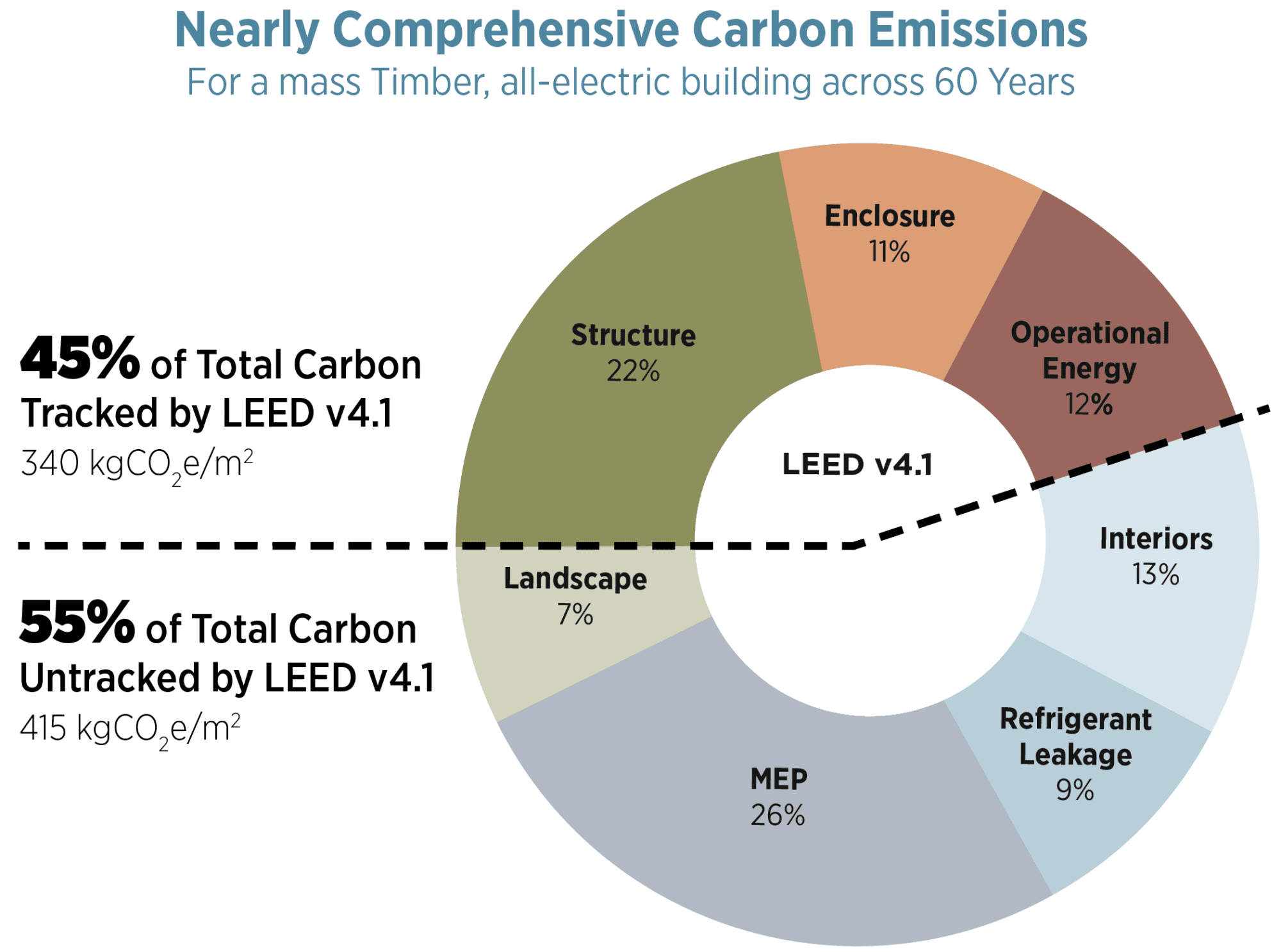

An all-electric, mass timber project was compared to the LEED v4.1 System as a framework. The analysis included operational carbon from energy use (but not time of use), plus the embodied carbon pollution of structure and enclosure, interior partitions and finishes, landscape and sitework, mechanical equipment, and anticipated refrigerant leakage.

LMN, MKA, and PAE engineers analyzed the pollution from an advanced building, including Mass Timber structure and significant energy use reductions from high performance envelope and mechanical systems, noting that a majority of carbon pollution is excluded from the LEED v4 rating system.

Only about 45% of the total carbon pollution associated with this building were considered within the LEED system, showing that the industry has advanced more rapidly than rating systems in the last decade. LEED version 5 includes a much broader carbon scope.

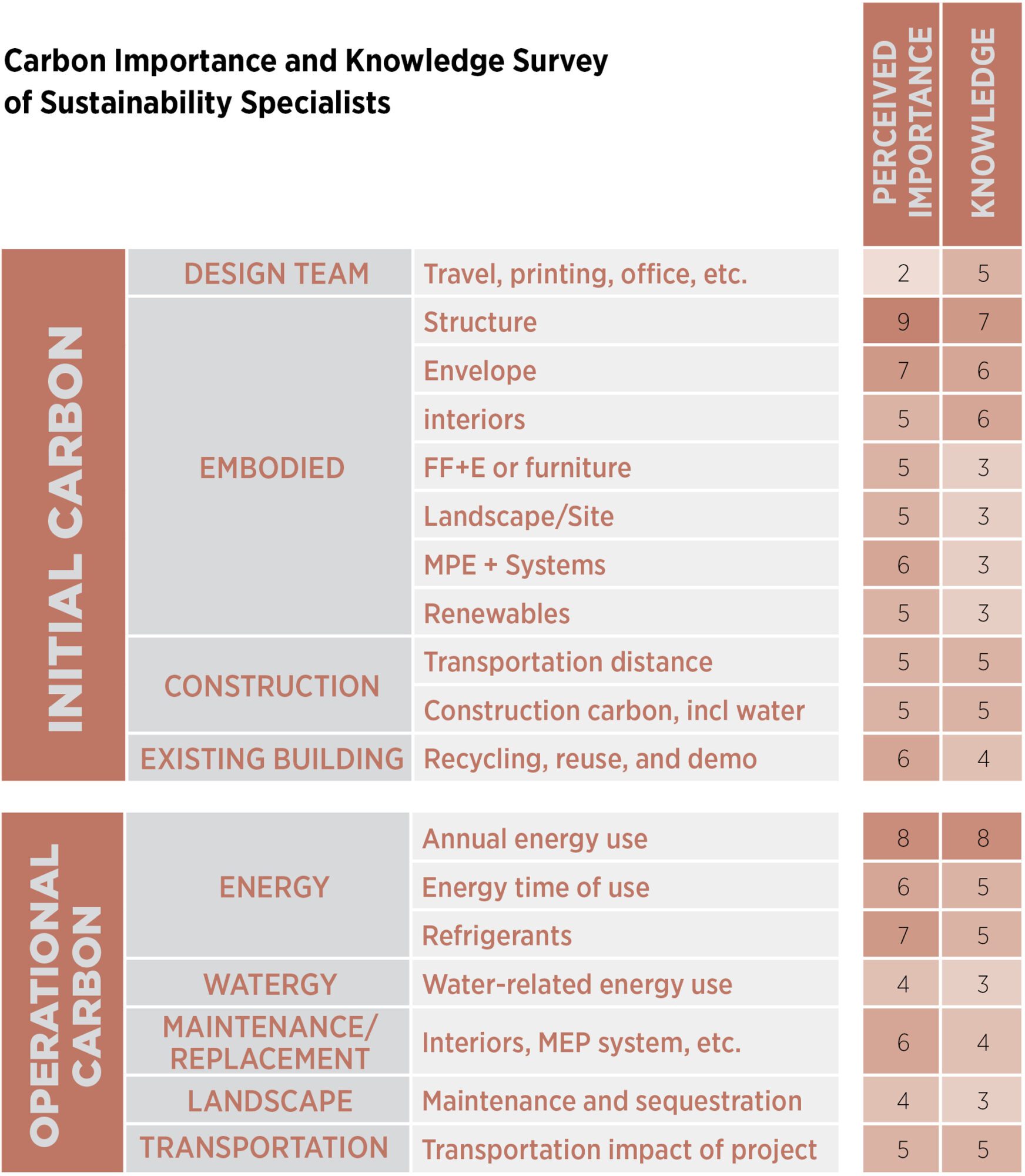

The gap also exists in knowledge about some areas: a survey of sustainability specialists illustrates these, even among the leaders within the profession. Each of these areas will be covered later in the series as we grapple with reducing our pollution.

Beyond energy use and structural embodied carbon, other sources can be a significant part of a building’s footprint and will be discussed later in the series. We know less about many of these areas, with ongoing research. For example, the MEP 2040 is exploring refrigerants and the embodied carbon of MEP systems, the Pathfinder and Carbon Conscience tools includes the impacts of landscape and hardscape, the CARE tool, which compare embodied carbon against operational carbon for building reuse, and the c.scale tool that includes many other categories.

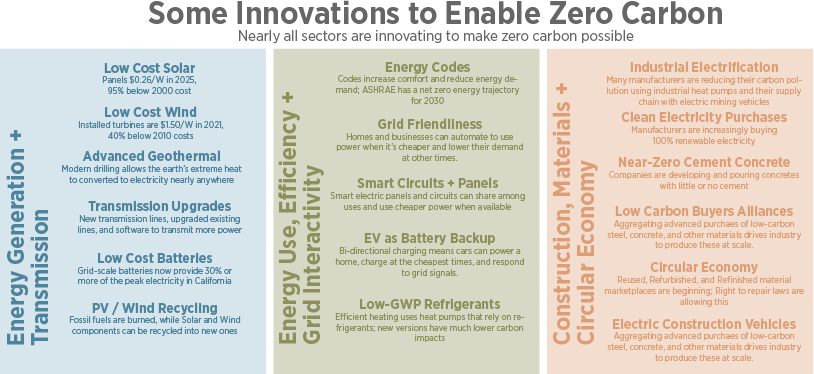

The good news that makes Zero possible in the future

It is impossible to summarize the depth and breadth of companies, investments, technologies, and products being developed to reduce or eliminate fossil fuel pollution. Since electrification unlocks massive global potential while solving the problem of climate change, private investments, government investments and regulations, and industry are all exploring the potentials of the new electric economy. Global investments in grids and storage, renewable and clean power, and energy efficiency is now double that of investments in fossil fuels.

Renewable Energy: Solar and wind are now the cheapest energy sources in most of the world and are attracting more investment than fossil fuels. Beyond solar and wind, renewable energy technologies are being developed that rely on heat deep in the earth, wave power, and more

Transmission Upgrades. Many groups are planning additional transmission lines to share power more widely and connect the most optimum solar and wind generation areas with customers. Existing transmission lines can transmit more power by reconductoring with higher voltage transmission lines and use software to transmit more power in existing lines.

Low Cost Batteries. Low-cost batteries are now powering buildings and the electricity grid when variable renewables are generating less power, taking up slack as fossil fuel generation is reduced.

Low-Carbon Buyers Groups: Structural and mechanical societies have committed to low-carbon products, and low-carbon buyers associations have committed hundreds of millions for electricity, steel, concrete, sustainable aviation fuels, and more.

Manufacturing: Products are increasingly being manufactured with 100% renewable electricity (sometimes co-located to reduce transmission infrastructure and connection queues) using heat pumps, industrial heating storage, waste heat, industrial heat pumps that reach 160⁰C and higher. Products are also being remanufactured, reused, or manufactured with high ‘clean’ recycled content and recyclability as part of a low-carbon circular economy. Many product categories have a wide variety of Environmental Product Data available, allowing comparisons of products for carbon pollution from manufacturing.

Mining and extraction. Massive electric mining and hauling equipment is being used.

Circular Economy. While clothing, kitchen equipment, and other items have been resold profitably for decades, industrial products, mechanical equipment, and an increasing number of items are now available, reducing the need for raw materials, transportation, and manufacturing.

Transportation. beyond personal EVs and micromobility, the transportation of goods in trucks, delivery vans, drayage, and ocean freighters now have options.

Building and Energy Codes: Energy codes across the US and world are significantly reducing energy demand, saving billions of dollars each year in energy costs for consumers, and also reduce the need for new generation infrastructure. Low-carbon codes such as CalGreen and Vancouver Bylaws require lower-carbon materials and buildings.

Refrigerants: Even as air conditioners are becoming more essential with climate change, low-carbon refrigerants are being developed, rolled out, and then required, with some lowering GWP by 95% or more.

Construction Carbon: Electric construction vehicles and R99 fuel blends are lowering construction carbon, along with hybrid construction generators for site power.

As discussed in Post 16, other changes in the building industry are reducing carbon pollution as well: policies and incentives for building reuse, adoption of electric vehicles and micromobility, land use changes, afforestation, and much more.

Tracking our progress

The AEC industry is working hard to identify and track its impacts and currently there is a need for additional, increasingly precise data. However, we know enough to target significant reductions currently. While we believe that zero carbon architecture is an impossible claim at the current moment, innovations toward that goal are part of the hard work of our industry and should be celebrated.

We think these are important considerations for carbon claims of products, buildings, and infrastructure:

- Clarity of data –Results should be presented with uncertainty ranges, and net zero discussions should be based on conservate estimates. This should include disclosure of the type and scale of data used: industry averages, location-specific, or other.

- Clarity of scope – All Net Zero claims need to be made with study scope specifically identified, and any missing or excluded scope noted.

- Cast a wide net – To avoid ignoring carbon sources, teams should include as many sources of carbon as possible for their study.

- Disclose forward-looking data. Many important data sources, such as future electricity emissions based on NREL’s Cambium are very useful, but provide different results than using industry averages for current electricity emissions. Many products will be produced with increasingly renewable electricity, meaning that renovations within LCA studies need not assume the same embodied carbon as from materials produced today.

- Disclose the timeframe of the study and any carbon discount rate. Studies covering 20 years provide very different results than studies covering 60. Some studies include a method of prioritizing near-term emissions reduction, such as using a discount rate.

- Disclose any negative sources of carbon – biogenic and/or carbon offsets – to ensure that attempts to sequester carbon are additional, take place over a meaningful time frame, and are long lasting.

Numerous guides have been created to promote strategies toward zero carbon, including:

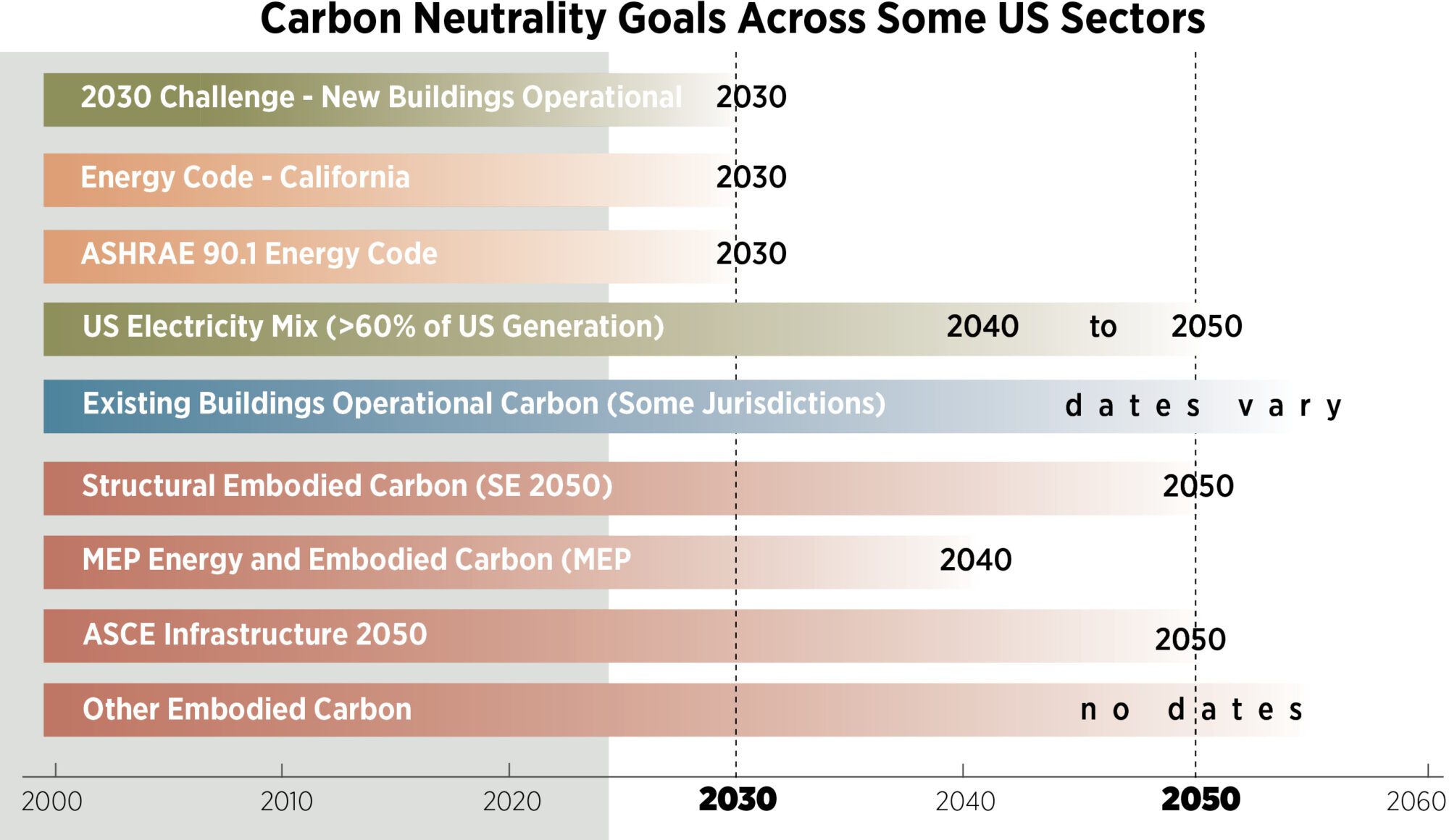

Many organizations have set sector-wide targets for carbon neutrality, including the 2030 Challenge (adopted by the AIA), ASHRAE 90.1 energy standards, a combination of US States and utilities committing to renewable energy, some states and jurisdictions adopting energy retrofit requirements, the Structural Engineers SE 2050, the MEP Engineering MEP 2040, and the Civil Engineers ASCE 2050 for Infrastructure.

Lastly, zero nearly always requires a negative carbon number since the act of building creates a carbon impact – these negative numbers often include biogenic carbon and carbon offsets. Both have the potential to reduce total atmospheric carbon, but their use in carbon accounting is controversial. Project teams striving for zero carbon architecture need to be aware of the arguments surrounding these topics and to clearly lay out any claims of negative numbers in their calculation, including the time frame anticipated for carbon sequestration. Post 08 explores this topic.

Think Global, Act Local: Office as Carbon Lab

Our offices can act as laboratories for innovation and experimentation, informing client conversations and pollution reduction strategies.

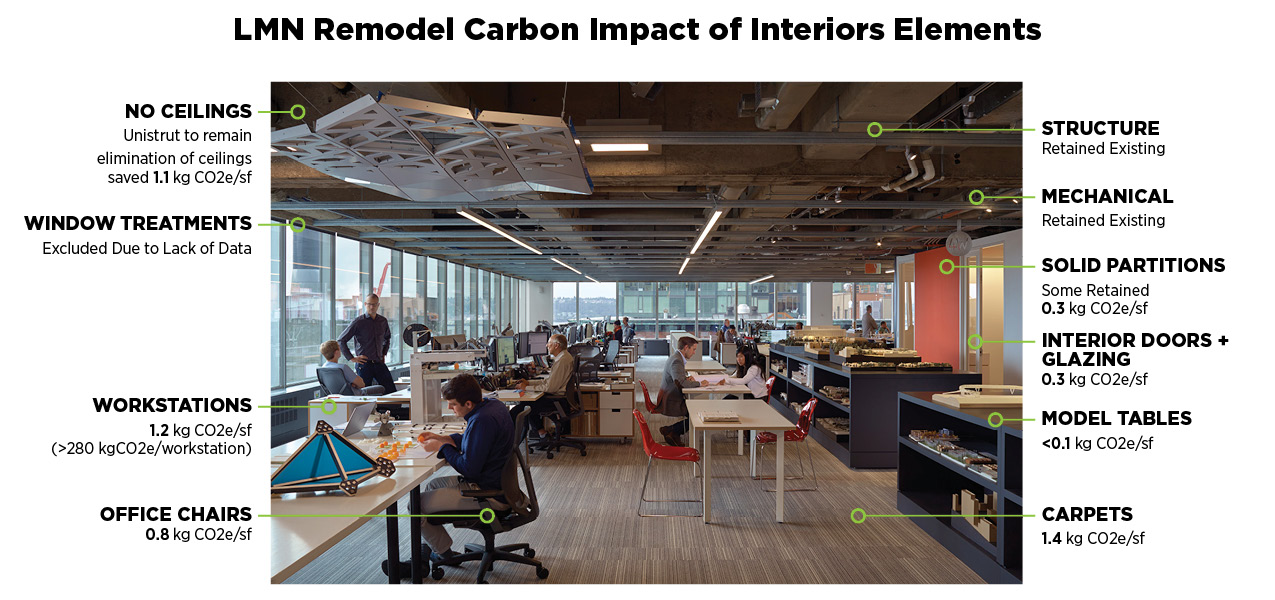

We chose our office for a detailed study of interior renovations’ embodied carbon impact. This has helped us become familiar with the relative carbon impact of common interior systems, especially the high impact of carpet, chairs and workstations.

As examples, studying the embodied carbon of our 2015 office remodel inspired articles and the creation of a public-facing interiors embodied carbon toolkit. We have also tested custom post-occupancy data tools on our own office first. Providing custom composting and recycling containers to improve usage rates, requiring sustainable lunch packaging from caterers, lowering energy use with controls, learning the benefits of motorized shades to provide daylight, and other efforts inform our daily conversations with clients, as well as the goals in our 2024 Sustainability Action Plan.

Calculating and reducing our office footprint is also part of exploration: we include business travel, operational energy use, purchasing and printing, employee commutes, waste/recycling/compost, and more using the advanced tabs for more detailed inputs within Berkeley’s CoolClimate Business Calculator. Using this tool, our office has an estimated footprint of around 600 tCO2e annually (pre-pandemic), or around 4 tCO2e per employee. From 2008-2012, we offset our carbon footprint using Bonneville Environmental Foundation, switching in 2013 to Forterra’s Evergreen Carbon Capture program where we planted trees each year that will remove carbon from the atmosphere over 100 years. We are switching away from tree-planting for carbon sequestration, back to using more rigorous and immediate offsets. This is largely driven by research for this series where we strongly believe now that carbon offsets need to be fully realized over a very short time frame, matched with the time pollution is released.

Many AEC industry offices reach net zero energy, certify to net zero carbon, track energy use, use salvaged and low-carbon materials, and engage in other experiments that give us daily insight into how we can steward the built environment towards carbon neutrality.

Please email any questions or comments to Kjell Anderson, kanderson@lmnarchitects.com

Thanks to our external collaborators and peer reviewers

Vincent Martinez, Arch 2030; Kristian Kicinski, Bassetti Architects; David Mead, PAE Engineers; Harry Flamm, Stantec

LMN Architects Team

Huma Timurbanga, Justin Schwartzhoff, Jenn Chen, Chris Savage, Andrew Gustin, Kjell Anderson

Posted: 06/16/2022

Edited: 01/08/2026

The text, images and graphics published here should be credited to LMN Architects unless stated otherwise. Permission to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes is granted as long as attribution is given to LMN Architects.