#sustainable, #waterfront

How Vancouver Greened Its Waterfront

The new Vancouver Convention Centre West holistically integrates a metropolitan downtown with one of the most spectacular natural ecosystems in North America. Certified as the world’s first LEED Platinum convention center, the project weaves together architecture, interiors, urban design, and landscape in a unified piece of the urban fabric that functions literally as a living part of both the city and the harbor.

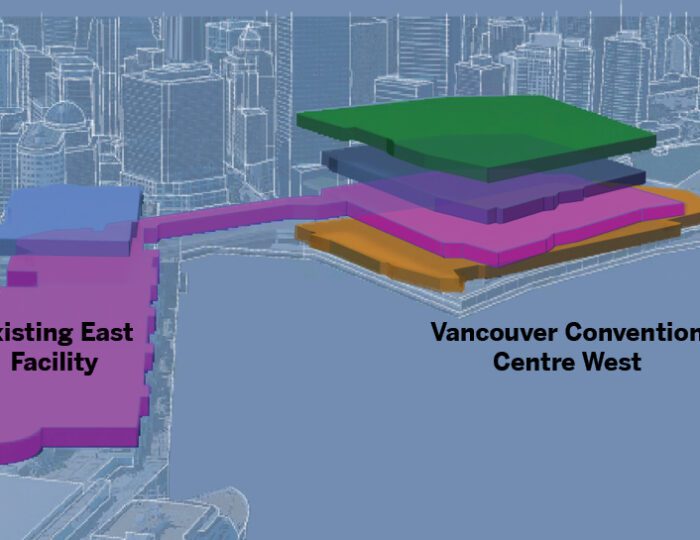

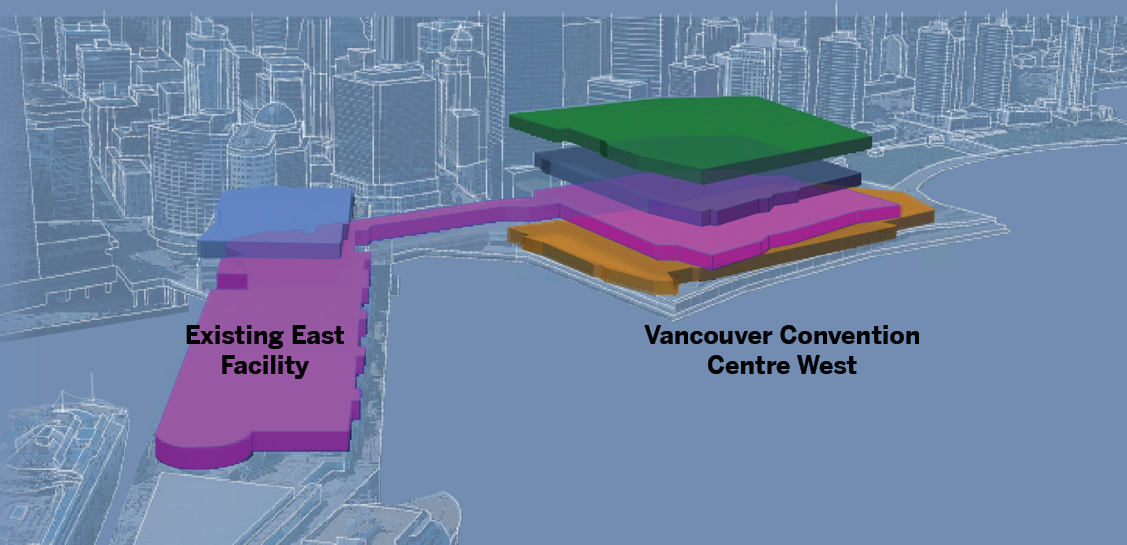

Reusing a former brownfield site, the development is approximately 14 acres on land and 8 acres over water, with 1 million square feet of convention space, 90,000 square feet of retail space, 450 parking stalls, and 400,000 square feet of walkways, bikeways, and public open space. Among other destination amenities, the project’s Jack Poole Plaza is the city’s first major gathering space on the water’s edge, and the permanent home of the 2010 Olympic Torch.

The convention center program emphasizes spaces for both public and private events, mixing the energy of convention visitors with the social life of the city. Urban spaces formed by the building’s landforms extend the downtown street grid to preserve view corridors out to the water. The public realm extends through and around the site, with continuous access to the water’s edge and explicit accommodations for bicycles and transit.

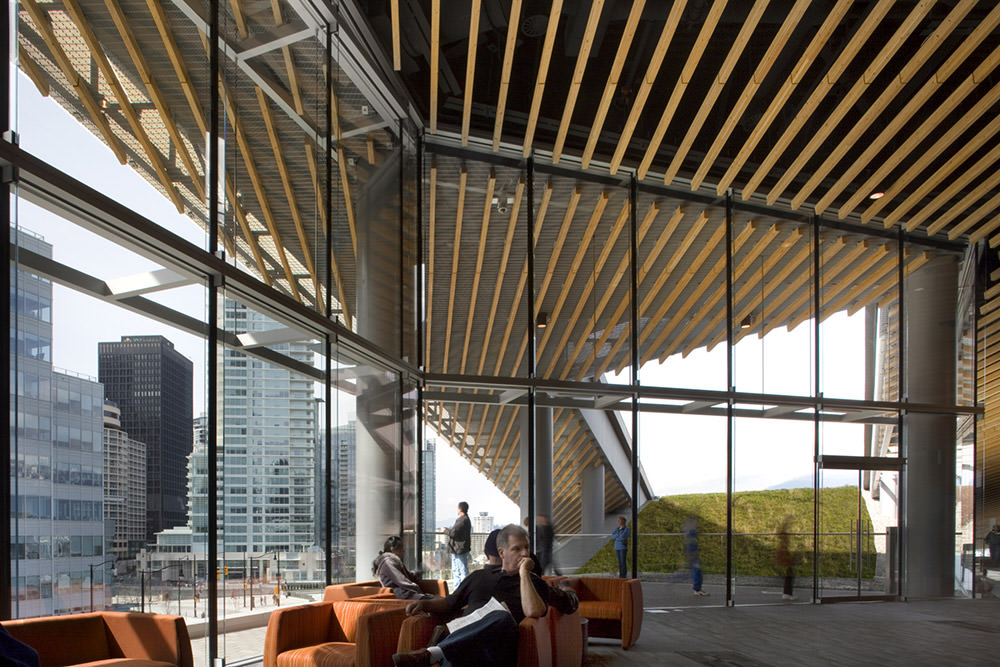

The building’s perimeter enclosure is an ultra-clear glass system, blurring the boundaries between exterior and interior functions. Sweeping views from the interior to city, harbor, and mountains visually reinforce the integration of context into the user experience of the building.

The project triples the convention capacity of Vancouver and presents a renewed identity for the city on the world stage, demonstrating deep currents of thought in the community about urban ecology and civic involvement. The facility has had a dramatic and measurable impact on the region, drawing larger conventions to the city than was previously possible, integrating wildlife into the urban core, and completing the urban planning goals for the Coal Harbour waterfront neighborhood that the city has worked toward since the 1980s.

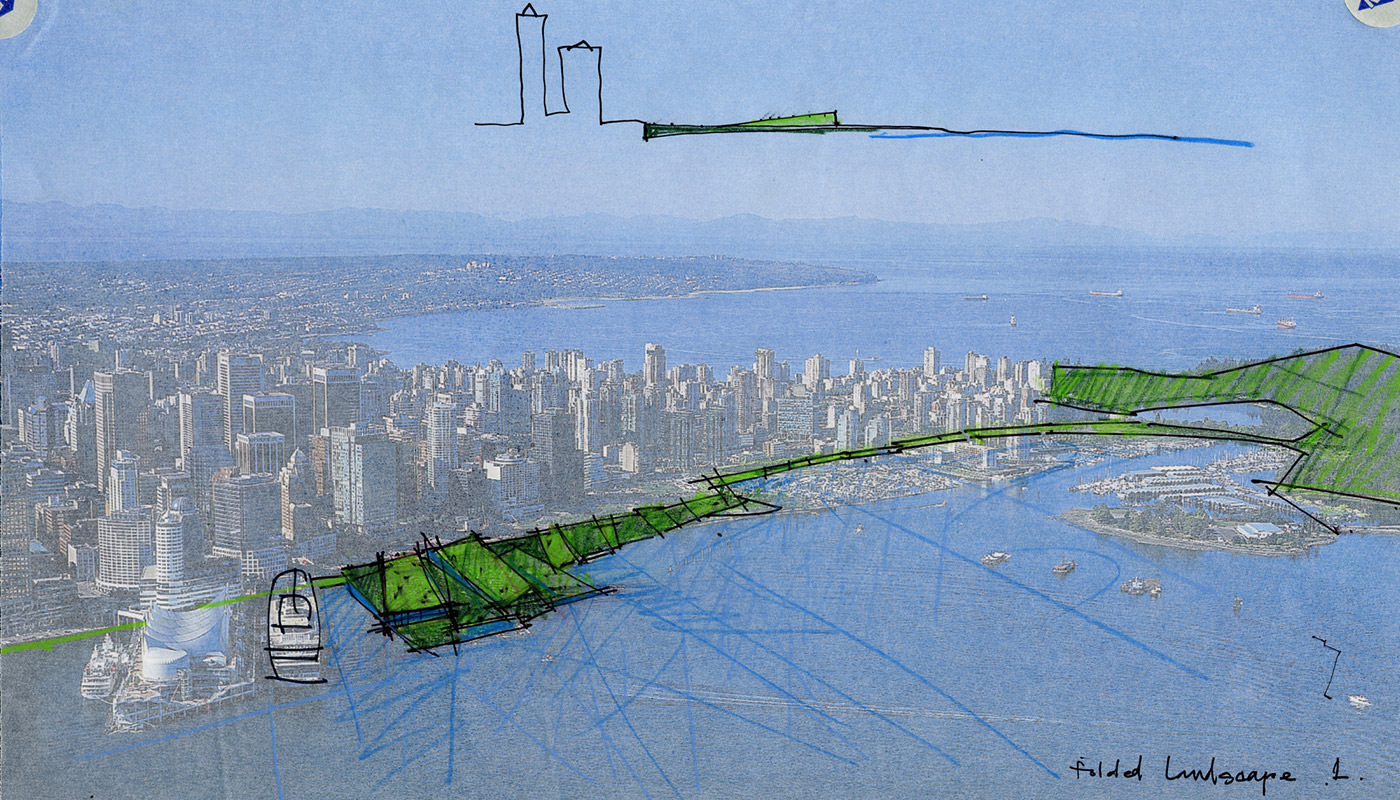

Regional & Urban Design Vision

The Coal Harbour neighborhood on the north shore of Vancouver’s downtown peninsula has been the site of multiple redevelopment efforts by the city since the 1980s. Historically an industrial district characterized by shipyards, lumber mills, seaplane manufacturing, and railroads, the area began to change dramatically with the construction of the Canada Place convention pier for Expo 86. As industrial uses moved out of Coal Harbour, the city set in motion a long-term plan to redevelop the area as a high-density mixed-use neighborhood, taking advantage of its desirable location between the financial district and 1000-acre Stanley Park.

Between 1995 and 2010, Coal Harbour experienced accelerated development of residential high rises. The city made a series of investments in the public realm to plan for a neighborhood of 9,300 permanent residents, including a high percentage of families with children; these investments resulted in a growing collection of waterfront amenities, including parks, marinas, a community center, and pockets of neighborhood retail.

The culmination of these efforts was the keystone development of an expanded waterfront convention center on a newly remediated site, acting as the city’s “front porch to the world” for the 2010 Winter Olympics and beyond. Where the original Canada Place and Expo 86 catalyzed a radical rethinking of the industrial waterfront as a dense residential neighborhood, the expanded Convention District built on 20 years of community planning efforts to remake the waterfront as a holistic, ecologically productive system.

The stated goal for the project was to “bring urban ecology into the downtown core,” and upon its completion in 2009, the City of Vancouver passed an initiative to become the “greenest city in the world” by 2020, releasing a 10-part action plan addressing carbon, waste, and ecosystems.

Sustainable Design Intent & Innovation

The design approach encompasses at once a single building and a new urban district, creating an ecologically connected experience that embodies all the diverse elements that define its local and regional location. Energy and water flows are controlled through high-efficiency systems and holistically integrated with local resources.

Environmental

Typical convention centers can create large energy and water demands as well as consume large areas of valuable land. The overriding project goal was for this facility and district was to showcase the values and priorities of the city by creating the most sustainable facility of its kind.

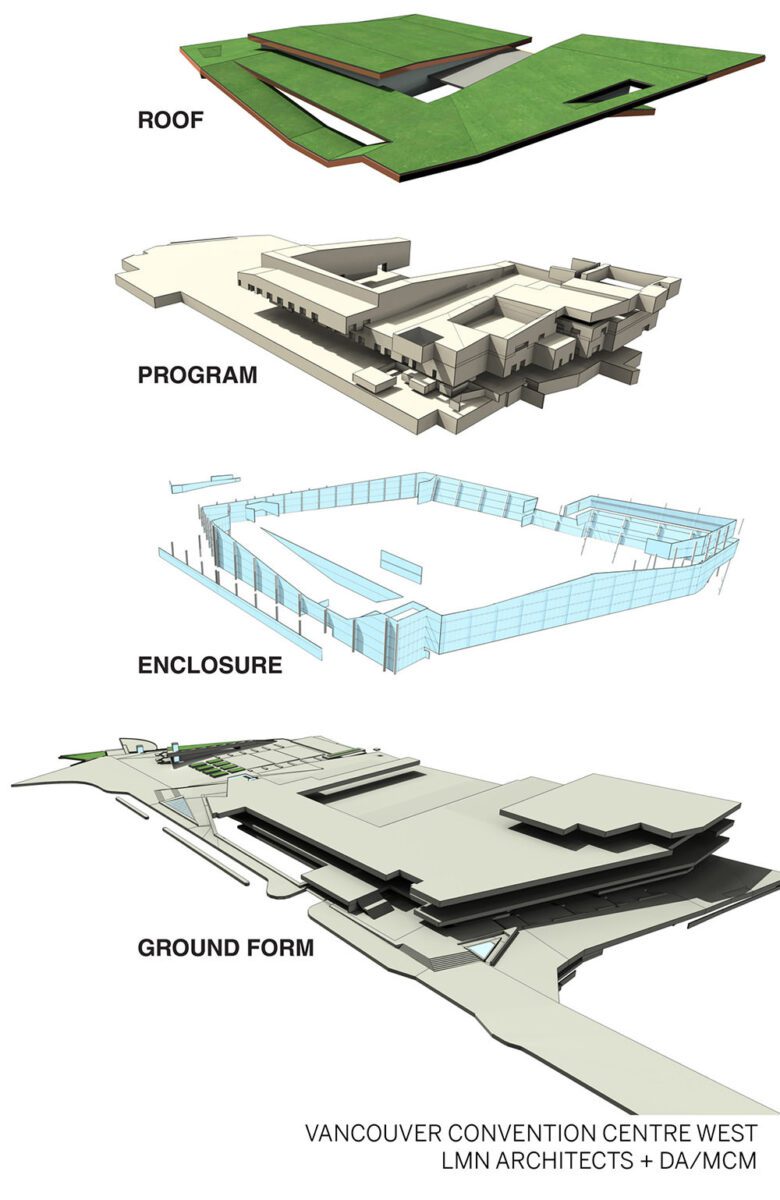

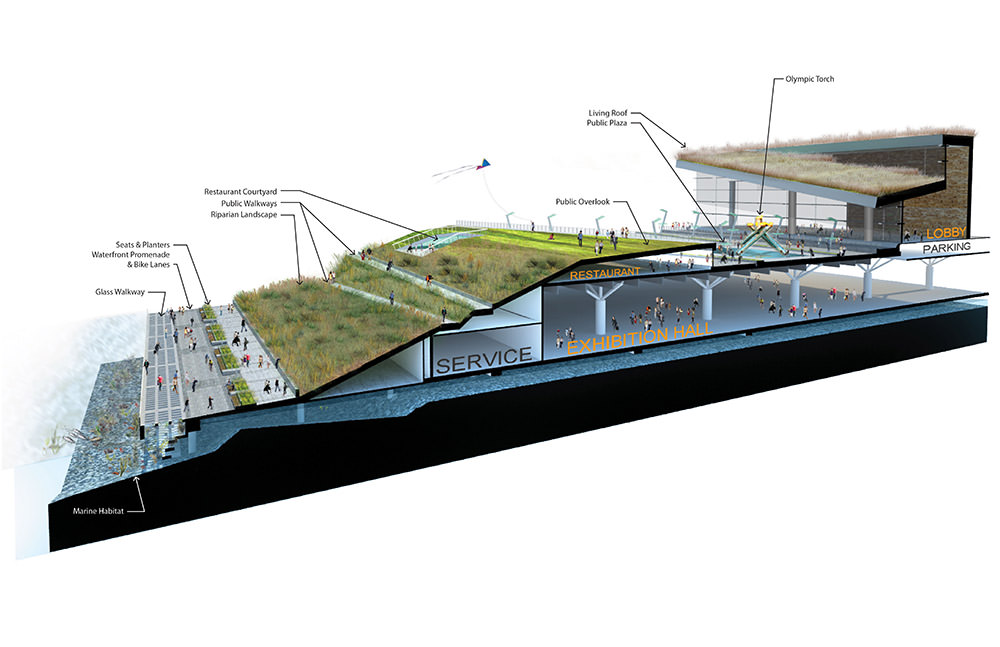

The major identifying feature of the district is the expansive green roof that formally continues through the public realm to the water’s edge. The large non-accessible portion contributes more meaningfully to the local ecology of the region as a habitat stepping stone linked to Stanley Park through a chain of waterfront parks. Views to the living roof occur throughout the district and interior spaces, including outdoor viewing platforms and educational kiosks.

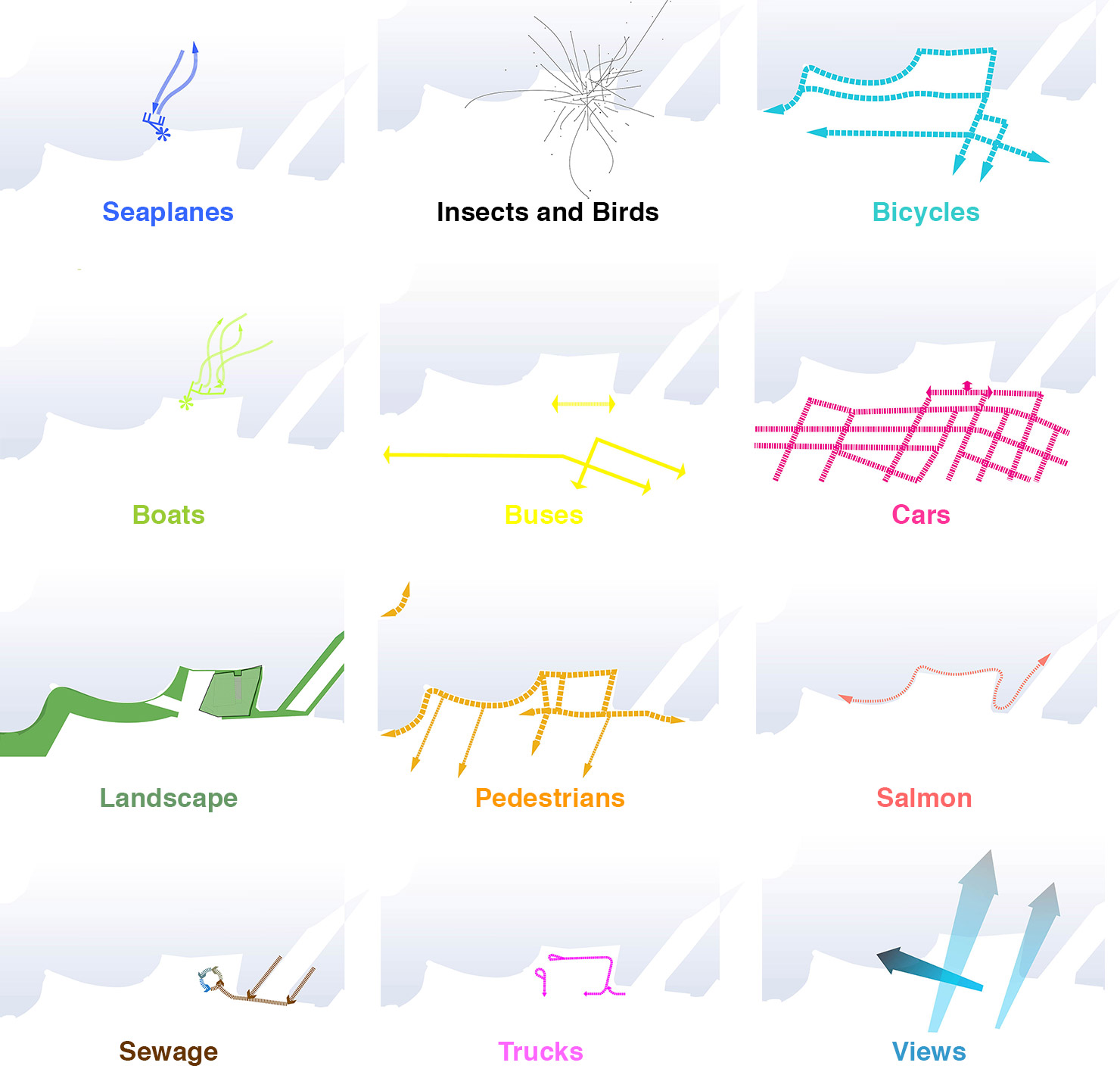

Less visible but equally productive is the marine habitat restoration, which provides rough concrete surfaces for marine life at multiple habitat depths, characteristic of local shoreline ecology. A diversity of large fauna are supported such as salmon, Dungeness crabs, and harbor seals. Salmon in particular are an integral part of the regional identity. Monitoring has shown a strong return of multiple salmon species as a result of the restoration.

Social

Design took place over a period of 3 years, with a highly inclusive public process. In addition to the client leadership, city agencies, and consultants, stakeholders taking part in the design included neighborhood groups, local tenants, environmental agencies, the natural resources industry, and First Nations. The extensive involvement of the community in the design through public process is manifest in both the feeling of local identity in the building as well as the highly accessible, civic nature of the convention district, which includes continuous public access to the water’s edge through walkways, bikeways, and plazas.

The project’s social longevity can be seen in its integration into the culture and daily life of the city. The district provides actively used public spaces as part of the urban core that interface directly with the city’s spectacular natural environment.

Economic

The Vancouver Convention Centre is recognized as one of the world’s leading convention centers, currently generating $215 million in economic activity per year and growing. The West facility tripled the capacity of the convention center as a whole. It also adds 90,000 sf of retail and restaurant space along the waterfront promenade, and infrastructure for future development over the water including an expanded marina and water-based retail. Visitors to the city are able to arrive at the site directly via an integrated sea plane terminal, perhaps the most dramatic way of witnessing one of the most spectacular urban landscapes in North America.

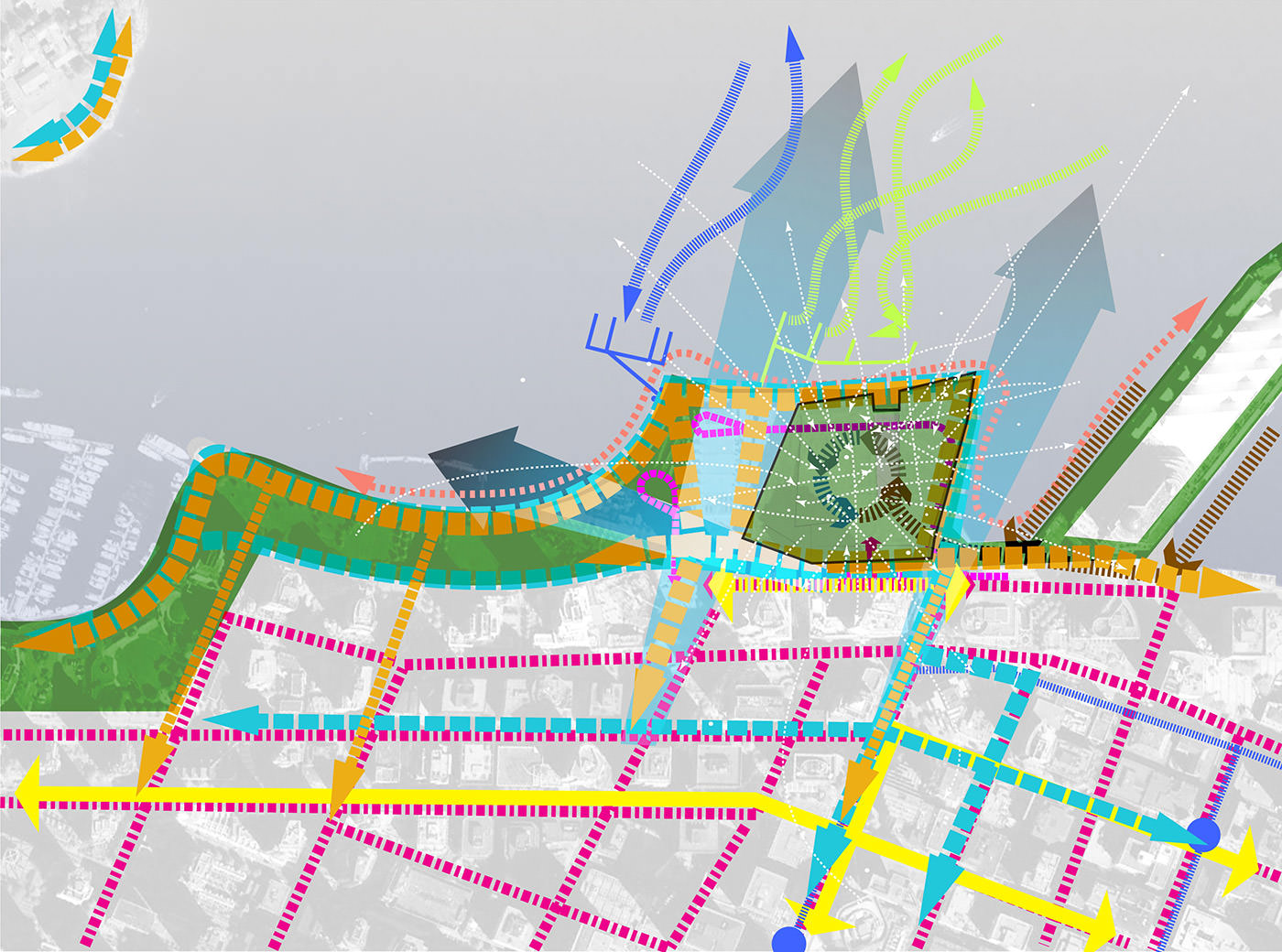

Urban Edge

The district reintegrates the urban neighborhood with the waterfront and surrounding parks and promenades by becoming the node where these connections overlap. Pedestrian and bicycle traffic are accommodated through and around the site, inviting users along the water’s edge or the urban street frontage. The district proves to be a very walkable environment with an overall Walkscore of 92 points.

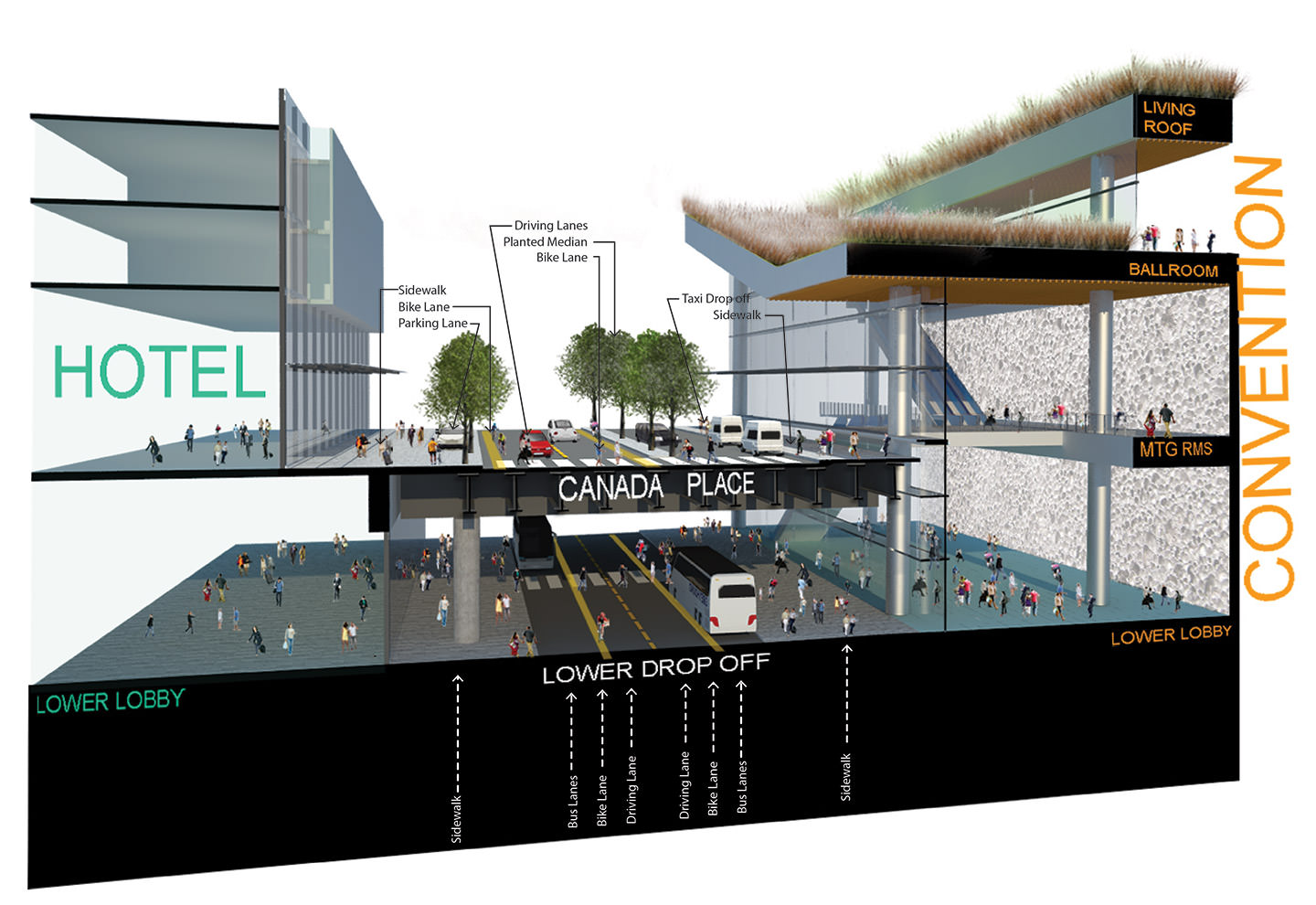

Parking demands and vehicular trips are further reduced for this area by the integral accommodation of transit facilities both on-street for the public bus system and an underground tour bus viaduct for convention attendees arriving at the subterranean lobby. 83% of the building population uses transit options other than a single occupancy vehicle. With 54 nearby public transit routes: 49 bus, 4 rail, and the skytrain the project scores a perfect 100 point Transit Score on the Walkscore website.

With 440 parking stalls provided in the below grade garage, the parking ratio works out to around 0.375/1000 SF or an occupant-to parking ratio of 18.8:1, based on an average show of 8,300 attendees.

- 90% of the above-grade building is enclosed in an ultra-clear structural glass curtainwall

- Entrances and exits coincide with urban intersections

- Access to over 54 different transit routes

- Lit interior creates “urban lantern” at night

- The convention district completes the Coal Harbour neighborhood, the city’s “front porch”

- Destination and jumping-off point for bicyclists and pedestrians on important city routes

- Canada Place Way equally accommodates car, pedestrian, and bicycle traffic; no-car lane

- 83% of district population uses transit options other than single-occupancy vehicle

- Promenade lined with 90,000 sf of walk-up retail plus marina retail

- Plaza directly embraces and interacts with public space, independent from the building

Marine Edge

Some 35% of the project is built on piles over the water, re-using an existing brownfield site with extensive contamination left over from a history of industrial uses and adjacent rail yard activity. The marine restoration effort returns the site to pre-industrial conditions, re-routing the shoreline around the building’s foundation piles. This is achieved by means of a custom-designed habitat skirt consisting of 5 concrete tiers on a sloping vertical frame surrounding the entire 1,500-foot perimeter, which emulate rocky surfaces for marine life to attach. Runnels dug into the tide flats beneath the building allow tide action and promote daily flushing. Concrete pipes and rip rap are strewn strategically on the sea floor, creating a variety of rock formations. Since the skirt was completed, scientists have continuously monitored the habitat and compared it with a nearby reference site consisting of undisturbed marine habitat. A March 2011 survey reported high species richness, such that the concrete tiers are almost entirely covered in barnacles and mussels, with an increasing number of sea urchins, sea stars, and juvenile and adult crab competing for space. “This increase in predators is a strong indicator that the habitat skirt is able to function as a typical intertidal habitat even though it is a near fully-suspended system,” the report states. The survey also observed large schools of chum, coho, and chinook salmon feeding on plankton and finding shelter in the skirt’s plant life.

- Concrete and rip-rock habitat reef modeled on local shoreline ecosystem conditions

- 5 concrete tiers cover the full 4-meter tidal range, providing rough horizontal surfaces

- 1,500 lineal feet of habitat returns former brownfield to pre-industrial conditions for marine life to attach

- 1,500 lineal feet of habitat returns former brownfield to pre-industrial conditions

- Runnels built into the tide flats beneath the building support marine life adapted to darkness and promote daily flushing of the reef

- Habitat skirt effectively re-routes the shoreline, protecting and restoring a salmon migration path

- Long-term research in place to monitor the development of the ecosystem as compared to an undisturbed reference site

Social Life of the City

Built in anticipation of the 2010 Winter Olympics, Vancouver Convention Centre West is thoughtfully planned to serve the public far beyond the timeframe of a single event. The design approach is to create a socially connected experience that embodies all the diverse elements that define its place, creating a public amenity of perennial value to all of Vancouver’s residents and visitors.

Jack Poole Plaza

Named for the late chair of the Vancouver Olympics Organizing Committee, the plaza is the city’s first gathering place on the water. Hosting the Olympic Torch for the duration of the games, the plaza is now the permanent home of the torch as a memorial to a defining moment in the city’s history. The plaza is continually programmed with concerts, public gatherings, formal and informal events.

Choices of Ways to Participate

A guiding principle in designing the district’s public space was to provide choices of ways to use the space. Even as a concert goes on in the plaza, the promenade and green space remain separate, with a variety of seating and eddy spaces available. There are dozens of ways to experience the views, gather with groups, travel through the site, and find activity or solitude.

Public Art

A $5 million budget for public art allowed for a diversity of sculptures, installations, and educational plaques to be included at key nodes of the promenade and plazas. Temporary artworks also help to ensure the public realm is a dynamic and engaging experience. These art pieces help to activate and celebrate the local culture of British Columbia.

Indoor/Outdoor Connections

The transparent perimeter enclosure provides strong linkages between interior and exterior public spaces. Interior circulation and prefunction spaces are placed around the perimeter, protecting the privacy of events within the building core while creating a connection between the activity of the building and the life of the city. In a radical departure from the majority of urban convention centers, the building enables feedback and interaction between visiting conventions and the public life of the city, beyond the commerce generated for private hotels and restaurants.

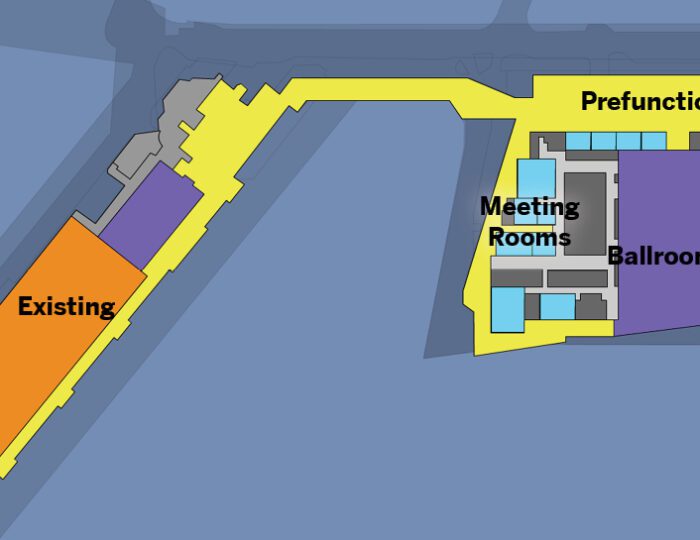

Interior Architecture

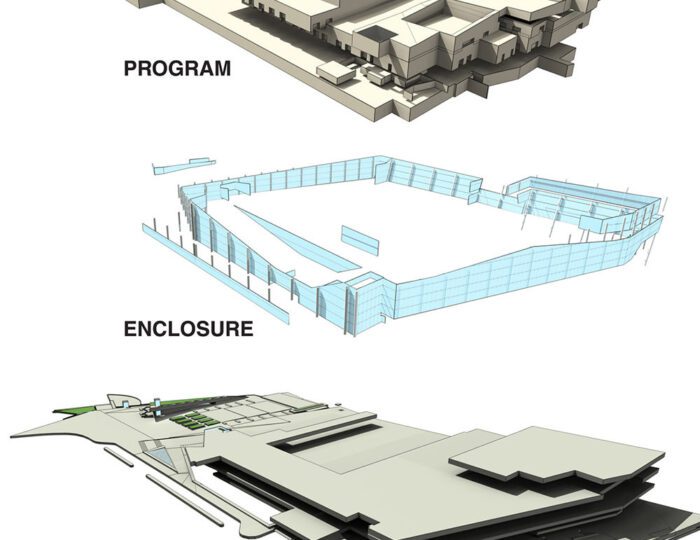

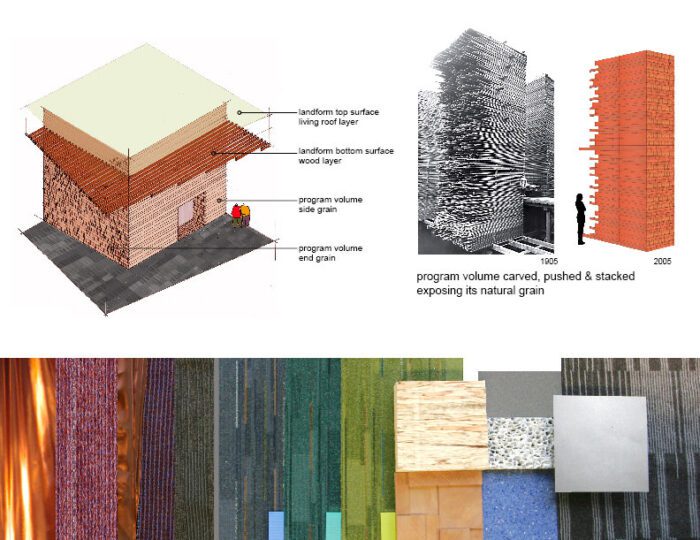

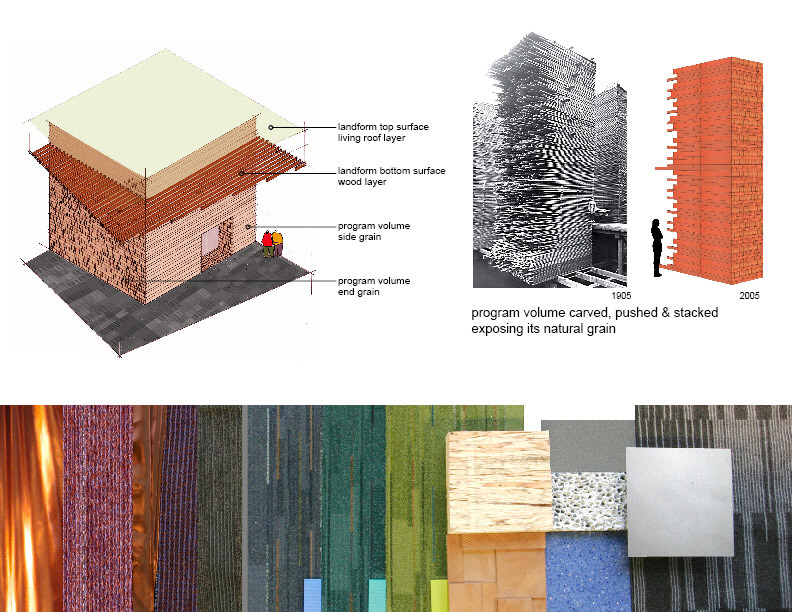

The building’s main architectural elements are the landforms, the program, and the glass skin, which intersect throughout the building in a variety of compositions. Within the interior, the landforms serve as the ground plane in some areas, and in others as the ceiling plane, creating a topographical experience throughout. Materiality is based around the use of indigenous British Columbia wood, recycled in the form of glulam and expressed in the strong directional lines of the ceiling plane as well as extensive wall cladding that simulates the texture of stacks of lumber. The living roof itself has no public access points, allowing it to develop as a fully functional habitat for migrating wildlife, while the landforms fold in specific ways to open views onto the roof’s lush vegetation from inside and outside the building.

The interior is constantly connected to daylight and views, setting up an extroverted, community- friendly relationship with the exterior and connecting the building’s interior experience with the life of the city and the waterfront. Transparency serves as an orienting device to provide directionality within the building’s program, anchoring each space to the unique views available from its vantage point. By night, the lit interior creates an urban lantern at the water’s edge.

A comprehensive strategy was developed for addressing indoor air quality, incorporating a sophisticated monitoring system that allows fine control over individual rooms based on occupancy rates and event types. The interior is fitted throughout with CO2, VOC, and humidity sensors, which can be monitored in conjunction with airflow, temperature, and lighting controls to optimize air quality on a room-by-room basis. Operators can control these elements via hand-held devices, which in many areas allow control of individual light fixtures and come with several presets for a variety of event types. Radiant flooring is used in the bulk of the program spaces, creating superior air circulation without significant energy use for ventilation. The west façade of the building (photo, top right) also includes operable windows and doors with dampers at the roof soffit, allowing natural ventilation under appropriate conditions.

All materials were selected to maximize recycled content, recyclability, durability, renewable material use, and local harvest and extraction. Interior finish benchmarks include 16% recycled content and 21% regional content, with 86% of construction waste diverted from the landfill.

Building Systems

The internal metabolism of the building draws many of its inputs from the site’s resident renewable resources, and makes dramatic reductions in energy and water use by both reducing consumption and utilizing renewable systems.

Energy

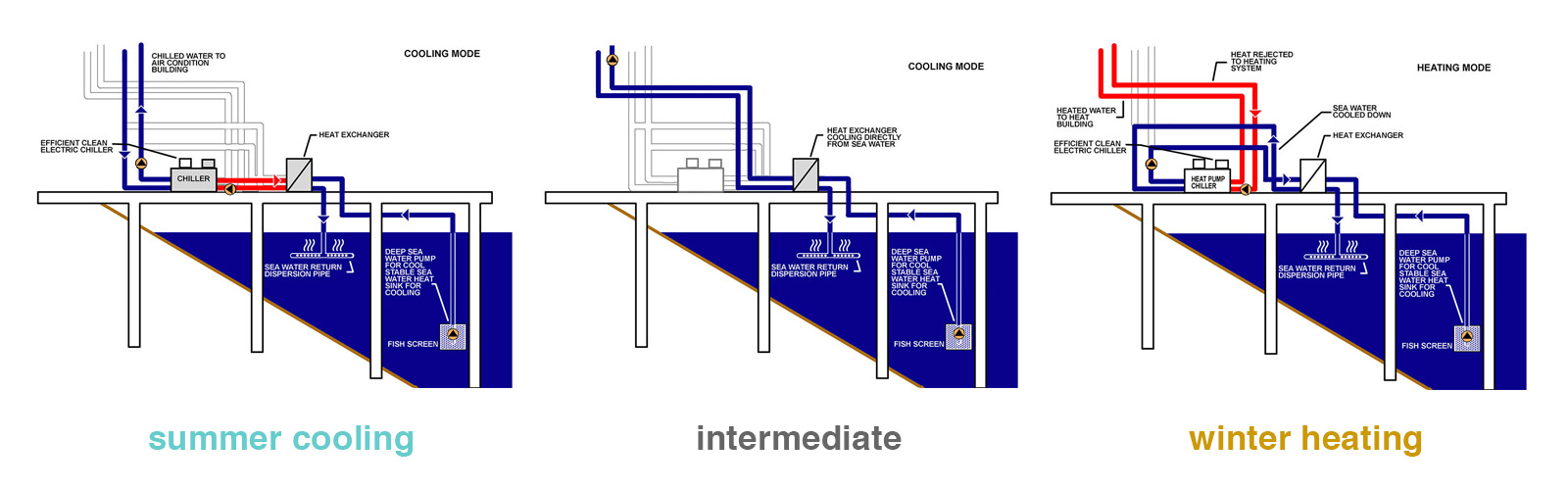

The building reduces energy use by 60% as compared with peer facilities. The electricity demand in the new facility is about half of the existing East facility, due to the use of high-efficiency systems such as a high-performance building envelope, efficient lighting design and daylight sensors, demand controlled ventilation and radiant heating and cooling.

On the mechanical side, the West facility uses seawater heat pumps as an integrated renewable resource, taking advantage of the constant temperature of the harbor to produce free cooling during warmer months and free heating in cooler months. This system decreases the amount of energy from the grid devoted to heating and cooling by about two-thirds. Overall, seawater heat pumps contribute a 30% reduction in energy use. Impact to marine life from these heat exchanges is minimal, due to the harbor’s strong tidal mixing and the availability of deep water for inlet and discharge pipes.

Water

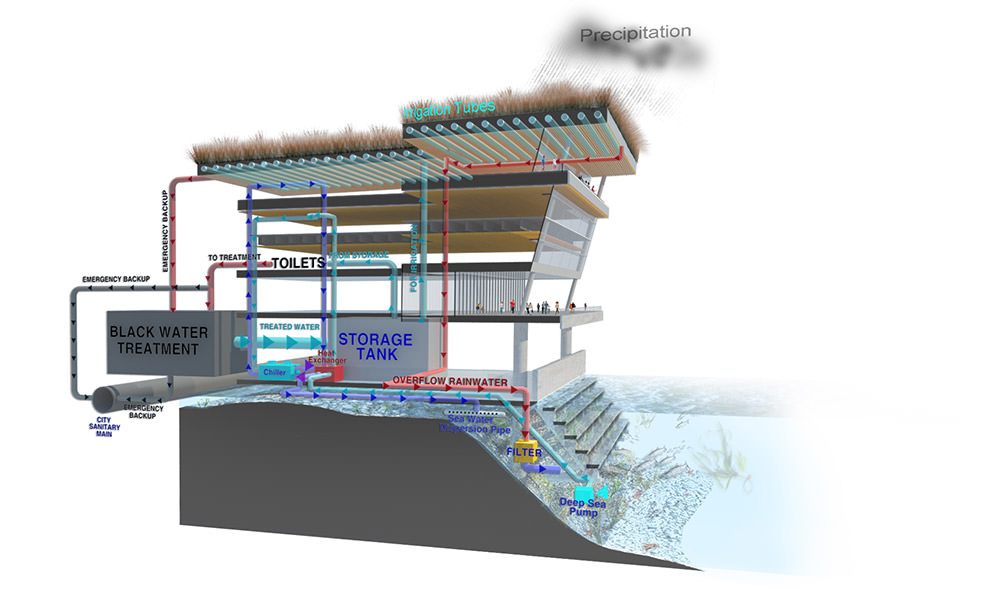

The estimated reduction in potable water use is 73% percent over typical convention centers, through a combination of high-efficiency fixtures and an extensive water reuse system.

100% of waste water from the building is treated and reused on-site through an on-site biomembrane reactor blackwater treatment system, which provides about 80% of the graywater needs for toilet flushing in the building as well as supplemental water for summer irrigation of the living roof. About 68% of total water use is from reclaimed sources. In frequent cases where the building effluent is not sufficient to maintain the biomembrane reactor, the treatment system pulls additional effluent from the adjacent cruise ship terminal and the city.

100% of precipitation is managed on site. All stormwater is filtered through the living roof and other on-site vegetation, then fed directly into the harbor. The growing medium for the living roof is designed to act as a sponge, retaining excess water for long periods and draining it in a controlled manner.

The water reduction strategy also includes a backup desalinization plant, which can provide additional irrigation to the living roof in time of severe need. The irrigation system is a sophisticated low-flow “drip” system that is only necessary during the summer months.

- Predicted Energy Use Index (EUI): 100 kBtu/sf/yr

- Energy use reduction from baseline: 60%

- Predicted Water Use Index (WUI): 7 gal/sf/yr (total site)

- Water use reduction from baseline: 73%

- % precipitation managed on site: 100%

- % waste water reused on site: 100%

Long Life, Loose Fit

The new Vancouver Convention Centre West is designed to operate seamlessly with existing facilities, and provide maximum flexibility of use throughout the life of the building. The facility accommodates multiple simultaneous events, as well as large single-user events.

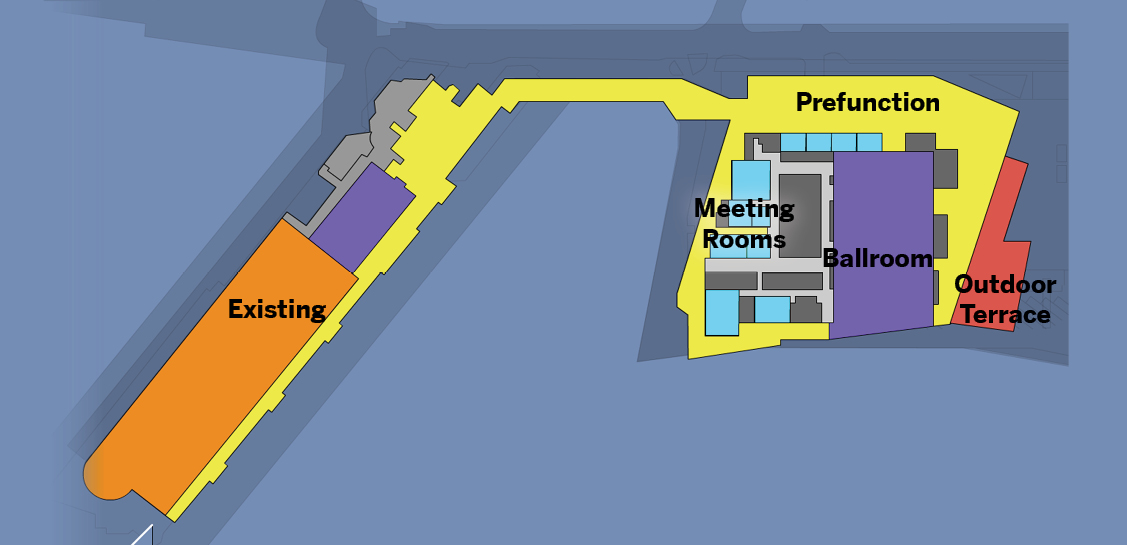

The Exhibit Hall, Ballroom, and Meeting Rooms adapt to a variety of different requirements for conferences, exhibitions and conventions, as well as an infinite variety of community events. The Exhibit Hall is set up on a 30’x30’ module that allows for efficient layout of 10’x10’ booths. The floor and ceiling are outfitted with a flexible system of utility service access pods, allowing a wide range of subdivision options. The Ballroom is set up to be one large space sub-dividable into 4 smaller spaces to meet the needs of the individual shows. The Meeting rooms occur in a variety of sizes and configurations, and several are sub-dividable.

An illustration of the building’s flexibility was its use as the International Broadcast Centre for the 2010 Winter Olympics. The building remains in high demand as a location for major motion picture shoots.

The building’s structural grid is also highly efficient, allowing for a range of interior renovation options. The structural system life expectancy is 100+ years, and the MEP system life expectancy is 50 years. One upgrade is required to make the facility net zero water ready.